India’s Politics Without Principles

Gandhi was cremated at Raj Ghat, on the Yamuna River, on January 31, 1948, the day after he was assassinated. Raj Ghat is a solemn space, a large, walled enclosure purposefully left open to the air and the white-hot sun of central India. It is set within an even larger park, with flagstone paths and shade trees - grandeur and greenery that that surprised me in a city as crowded as Delhi. Yet Raj Ghat itself is true to the simple life that Gandhi himself chose. As you walk around the upper level, on a path bordered by flowers and creeping vines, you can see the square platform in the center that marks the site of Gandhi's cremation. The black marble is so smooth that it reflects and extends the eternal flame that burns at one end of the monument, like a torch lighting the way forward in the dark of night. The red soil of his dear homeland surrounds the marble samadhi, as in life Gandhi rejected the green lawns of the English colonialists, choosing instead to leave the grounds of his residences in their natural state.

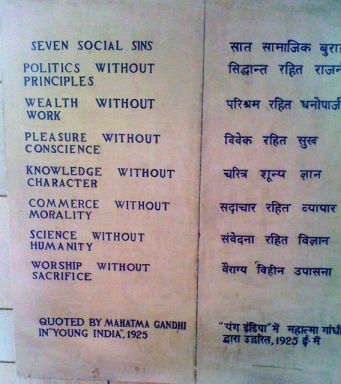

To enter Raj Ghat, you must remove your shoes. This is a sign of respect, one that I honor, but I admit to never having pictured myself meeting my idol in sock feet. It was in sock feet, however, that, in the cool shade of the thick stone walls, I walked the perimeter of the memorial. On the walls of the memorial are quotes from Gandhi, inscribed in the many languages of the Indian people as well as other world languages. Raj Ghat is a contemplative place; in concert with this, visitors are encouraged to circle the memorial three times. My first time around, near the marble platform, I stopped short. Before me, inscribed in black on the red sandstone wall, were words of deep truth, Ghandi's "Seven Social Sins," first published in 1926 in the newspaper Young India.

Gandhi's Seven Social Sins remain apt nearly 100 years later. They are:

POLITICS WITHOUT PRINCIPLES

WEALTH WITHOUT WORK

PLEASURE WITHOUT CONSCIENCE

KNOWLEDGE WITHOUT CHARACTER

COMMERCE WITHOUT MORALITY

SCIENCE WITHOUT HUMANITY

WORSHIP WITHOUT SACRIFICE

Mahatma Gandhi's words have stayed with me. Unlike the foreign dignitaries who visit Raj Ghat, I did not receive a khadi scroll imprinted with the Seven Social Sins. But they are written in my heart as distinctly as they are carved on that sandstone wall.

Certainly, the words were fresh in my mind later that afternoon at a meeting with Indian human rights activists. Over cups of masala tea, these human rights defenders told us about the alarming rise in discrimination and violence against religious minorities - particularly Muslims and Christians - in various states across India, including Gujarat, Orissa and Karnataka. While discrimination and violence against Muslims has long been a problem in India (including communal attacks targeting Muslims in Gujarat in 2002 that killed nearly 2000 and displaced as many as 140,000), these courageous human rights activists have documented the increasingly systematic discrimination and violence in the name of counter-terrorism since a series of bombings in 2007 and 2008. One group, Act Now for Harmony and Democracy (ANHAD), published a report in 2011 containing the testimony of scores of Indian Muslims at a People's Tribunal on the Atrocities Committed Against Muslims in the Name of Fighting Terrorism. As they described their experiences, as well as the impunity enjoyed by security forces and non-state actors that targeted religious minorities in the name of counter-terrorism, I thought again of Gandhi. Allowing human rights abuses to be committed against a broad category of people in the name of the fight against terrorism is indeed practicing "Politics Without Principles".

Later in 2011, and partly as a result of what we learned at this meeting, The Advocates for Human Rights made a submission to the Human Rights Council for the 2012 Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of India. Our submission, made jointly with the Indian American Muslim Council in the United States and the Jamia Teacher Solidarity Association (along with input from other Indian human rights organizations) in India, addresses India's failure to comply with its international human rights obligations to protect members of minority groups.

Additionally, our submission highlights the failure of the Indian government to adequately investigate and effectively prosecute perpetrators of human rights violations against members of minority groups.

I was in Geneva on May 24 for the Second Universal Periodic Review of India. The Indian government sent a large delegation, headed by the Attorney General. India clearly viewed the UPR process as both serious and important. The Human Rights Council is a human rights mechanism designed to be an interactive dialogue between governments. I was gratified to see Human Rights Council delegates from 20 countries address the issues raised in our submission, including the recommendation from the United States to "Ensure that laws are fully and consistently enforced to provide adequate protections for members of religious minorities..."

Geneva, Switzerland

The Human Rights Council made 169 recommendations to India. The government promised to respond "in due time" but no later than September 2012.

India's large and religiously diverse population makes it one of the most pluralistic societies in the world. The Indian Constitution provides all citizens with the "right to equality before the law," the right to "the prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth", and the "right to freedom of speech and expression". Further, it specifies that "no person who is arrested shall be detained in custody without being informed, as soon as may be, of the grounds for such arrest" and that every person arrested be presented to the nearest magistrate within 24 hours of the arrest.

India has made great progress in setting up a domestic legal framework to protect human rights and must be commended for that. India must now end the practice of "Politics Without Principles" and implement and effectively enforce these laws in a manner that protects the rights of members of its religious minority communities.

By Jennifer Prestholdt, Deputy Director and International Justice Program Director